South America´s camelids: Meet this fascinating group of highly adaptive mammals

The four camelids of South America can be easily confused with one other due to their similar appearances and behaviors. By observing and studying them in depth however, the characteristics become apparent that make these camelids so well adapted to the extreme climates and territories they respectively inhabit. Each camelid also plays a fundamental role in its ecosystem.

Camelids are a unique family, comprising six incredible species. Four of these inhabit South America: the guanaco, the vicuña, the llama and the alpaca. Their differences and similarities are surprising, but so are their origins. Guanaco and vicuña were first domesticated by Andean settlers more than six thousand years ago. Llama and the alpaca are hybrid species that resulted from this process. The territories inhabited by the guanaco and the vicuña are as diverse as the animal´s own curious characteristics. In this article, we delve into the world of these even-toed ungulates.

An interesting past

The Camelidae family is comprised of the guanaco (Lama guanicoe), the vicuña (Vicugna vicugna), the llama (Lama glama) and the alpaca (Vicugna pacos). The Camelidae is estimated to have originated from North America 40 million years ago, with the Camelinae subfamily spreading to South America and Asia 3 million years later, according to, research published in the University of Chile magazine Avances en Ciencias Veterinarias (Advances in Veterinary Science.)

“The camelid family as we know it today originated in North America and from there spread to different parts of the world,” explains the ecologist and Chilean camelid expert Agustín Iriarte. “They have unique qualities, such as the ability to acclimatize to desert landscapes, being able to survive on very little water and digest tough grasses that prove difficult for other herbivores.” Iriarte is general manager of the Environmental Consultant Flora & Fauna Limitada and is the author of more than 20 books on natural history.

“North American camelids disappeared 10 to 12 million years ago. In South America, the species evolved into the guanaco and the vicuña in South America, whilst on the Asian continent it evolved into the two-humped camel (Camelus bactrianus) and the dromedary (Camelus dromedarius),” writes the curator of the Chilean National Museum of Natural History (MNHN), José Yañez, on the museum´s website.

Approximately 6,000 to 7,000 years ago, Andean people began to domesticate the guanaco and the vicuña through reproductive selection, resulting in llamas and alpacas, respectively. Some experts believe this process could have begun as long as 10,000 years ago ago.

“In the most recent studies,” Iriarte explains, “evidence has been presented of the Tiahuanaco empire producing alpaca from vicuña and the Quechuas producing llama from guanaco. These ancient peoples began to domesticate animals by genetically selecting them so that the alpaca, for example, was more patient and docile or had special coloration. The llama, on the hand, was bred to be able to carry heavy loads”, says Iriarte.

Andean people continued to cross-breed these two species of wild and domestic camelids, the most common crossing being a llama with an alpaca, resulting in an animal known as a wari.

“For example, if you cross a vicuña with an alpaca, the resulting specimen is fertile, since it has a very high consanguinity (common ancestor) percentage of 99.9%. Thjs is referred to as a paco llama. Much more common, however, is the crossbreeding of a male llama with an alpaca,” the ecologist explains.

Today, wild camelids are most likely of wild origin: the guanaco or the vicuña; while llama or alpaca are most likely to be found accompanied by a shepherd. Below we share more details and information to help you identify the respective species.

South American camelids in the present day

Distributed across countries such as Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Argentina, Bolivia and Paraguay – South America´s camelids inhabit drastically different climatic conditions and altitudes. They have evolved with fine fiber coats to help them survive the harsh altiplano winters, the Chilean high altitude puna region or the harsh weather and often sub-zero temperatures of Patagonia.

“Chile´s camelids have an extraordinary capacity to adapt to their diverse respective climates,” says Iriarte. In winter, at 5,000 m above sea level, I have seen healthy vicuñas grazing without any problem with snow on their backs. Part of the adaptation they have to these climatic conditions has to do with the very fine fiber of their coats. Amongst hoofed animals, there´s is considered the finest fiber in the world.”

Camelids are artiodactyl or ungulate mammals, meaning they have two toes, a hoof and a cushion on the ball of their foot. Ungulates play a vital role in maintaining a balanced ecosystem by protecting the soil and dispersing seeds.

“When I was studying my doctoral thesis in Torres del Paine,” Iriarte explains, there was a fence that separated a neighboring sheep ranch from the national park with its wild guanaco population. There were more herbivores per hectare in the national park than on the ranch. Despite this, the ranch´s vegetation was completely chewed down, whilst that of the national park was intact and in excellent condition. The reason is that the guanaco has inhabited that Patagonian steppe for millions of years. It has evolved eating different types of shrubs at different times of the year, feeding in balance with the plants´ own growth. On the other hand, sheep eats only one type of plant, coirón (a tufty yellow grass) which completely imbalances the ecosystem.”

In addition to the important role wild camelid have in moderating the growth of vegetation, they are a key component of the trophic chain. Camelids constitute a fundamental dietary component of their main predator, the puma, as well as a food source for carrion feeders such as the condor.

Poaching, attacks by dogs and diseases such as scabies are the main threats to guanaco and vicuña. Different preventative conservation measures are in place to limit this impact.

“Due to excessive vicuña hunting,” Iriarte relates how in 1967, “The Agreement for the Conservation and Management of the Vicuña became the first pact in South America to control the commercial trade of a given species. Signatory countries today include Peru, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile and Ecuador. We must do everything possible to protect the vicuñas and guanacos in South America,” Iriarte adds. “They are our cultural heritage and are unique species.”

Identifying South America´s camelids

Guanaco (Lama guanicoe)

The guanaco is distributed throughout central Peru, western Bolivia and Paraguay, as well as much of Chile and Argentina. In Chile, this mammal is found from the foothills of the northern Arica and Parinacota region, to Tierra del Fuego and the islands of Hostes and Navarino. It commonly lives up to 3,000 m above sea level, but has also been observed at altitudes in excess of 4,500 m.

This species is considered the largest wild ungulate in South America, measuring between 1.2 and 1.75 m from its head to the trunk. Its tail can reach up to 25 cm.

The guanaco can be distinguished from the llama by its distinctive brown wool on the upper side of its coat and white wool on the underside as well as its black face. The coloration of the guanaco´s pelage allows it to camouflage itself in deserts, scrublands, and steppes. The animal mainly feeds on fungi, grasses, shrubs, and trees.

Guanacos exhibit social behavior, evident in the formation of groups of a single male and several females. They also form groupings exclusively composed of non-reproductive subadult males. Males are also known to exhibit solitary behavior.

“In general in Chile, the guanaco is considered Vulnerable (VU),” comments Iriarte of their protection status. “Only in the Aysén and Magallanes regions are they not endangered due to their abundance. Guanacos are most abundant in Tierra del Fuego due to the absence of predators “

*Source: Iriarte, A. 2021. Guide to the Mammals of Chile. Chile, Second Updated Edition, 236 p.

Vicuña (Vicugna vicugna)

The vicuña has two subspecies: Vicugna vicugna vicugna and Vicugna vicugna mensalis. The animal is found in the mountain ranges and altiplano of Chile, Bolivia, Peru and Argentina. There are also introduced specimens in Ecuador.

“In Chile, the vicuña is distributed from the Arica and Parinacota Region to the Atacama Region, covering all of the Chilean altiplano area, with its southern extension terminating in the Laguna del Negro Francisco, in the Nevado de Tres Cruces National Park,” Iriarte explains.

In Chile the animal has been observed in steppes and deserts between 3,500 and 5,500 m altitude.

The vicuña is the smallest of the South American camelids, measuring between 1.50 and 1.6 m long from head to tail, with a tail of up to 15 cm and a height of 80 cm to the withers (measured from the floor to the shoulder blades).

The vicuña´s coloration is similar to the guanaco, yet its face is the same brown colour as its body. It also has a tuft of hair that protrudes from its chest and flanks.

Theis herbivore feeds mainly on grasses and coirón and its conservation status is Endangered (EN).

*Source: Iriarte, A. 2021. Guide to the Mammals of Chile. Chile, Second Updated Edition, 236 p.

Llama (Lama glama)

This shy domestic camelid inhabits desert areas in southern Peru, western Bolivia, northern Chile and Argentina. It is often employed by humans as a pack animal and is capable of carrying up to 30 kg of weight on long and difficult journeys. The animal is also a source of wool and meat.

The llama can measure up to 1.20 m in height, and 1.20 m from head to tail, with a tail of approximately 20 cm.

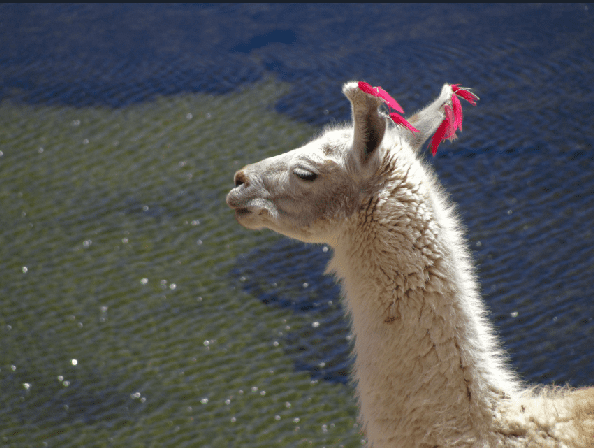

Unlike the guanaco, its pelage is long and abundant, but its wool still falls short of the alpaca´s in terms of length. There are two types of llamas: the khara or “hairless” variety, with hairless face and lower limbs; and the chaku or ¨hairy¨ variety with its pelage covering its body.

The llama´s color can vary between completely white, black or brown, or a spotted combination of these colors.

The llama´s diet is composed of grasses and shrubs.

*Source: Vaccaro, O., Canevari, M. 2007. Guide to Mammals of Southern South America. Argentina, First Edition, 424 p.

Alpaca (Vicugna pacos)

The alpaca is distributed domestically in the altiplano in southern Peru, western Bolivia, northern Chile and northwestern Argentina; where it provides a source of wool and meat.

Slightly larger than the vicuña, the alpaca can measure up to 90 cm in height and 1.50 m from head to tail.

The alpaca differs from the llama in that it has a long neck, short muzzle, and long, fine, abundant hair. Its neck, body, arms and thighs have long and soft wool. This same wool forms long forelocks, meaning their eyes are almost covered.

Two distinguishable varieties exist: one with long, abundant and soft wool called a suri, and the other with short and coarse wool called huacaya.

The alpaca is a herbivore and grazes on tender grasses. Its coloration is uniform but can vary by animal between white, dark brown or almost black.

*Source: Vaccaro, O., Canevari, M. 2007. Guide to Mammals of Southern South America. Argentina, First Edition, 424 p.

Keen-eyed observation

In Patagonia, specifically in the Torres del Paine National Park or in the Patagonia National Park, guanacos are part of the landscape. Here it is possible to observe them in all their beauty, and witness their behaviors in their natural habitat.

“In winter, the guanaco migration is a magical sight. It is a small and very local,” explains Sergio Godoy, “but we can see how they move through the landscape looking for suitable pastures, often finding them in unexpected places.”

“The summer is very different,” Godoy continues. In these months the guanaco head to the higher pastures once the snow has disappeared. Here you witness large groups of guanacos with their newborns.” Godoy is the Territorial Content Manager at Explora, and adds that, in the Explora Torres del Paine Conservation Reserve it is possible to observe guanaco in large groups.

In the Andean altiplano, vicuñas pick peacefully through a landscape of bofedales, wetlands and salt flats. Domestic camelids are most likely found walking neatly in line one behind the other, or accompanied by shepherds. Between the Atacama and Uyuni to the north it is very common to see llamas in the different towns, Godoy explains.

In Peru´s Sacred Valley and the site of Machu Picchu, the continued interaction of domesticated llamas and alpacas with local people is a relationship that has lasted many centuries.

“The interaction of llamas and vicuñas with humans is very special,” explains Godoy. “In the Sacred Valley it is a special relationship built on respect. The Aymara and Quechua languages even have words which shepherds use to address these animals as companions rather than as beasts of burden. This level of respect is noteworthy.”

Nature lovers from all over the world come to the South American continent to observe its domestic and non-domestic camelids in their respective habitats. Many make the comparison with Africa, believing these camelids to be every bit as spectacular as other hoofed mammals such as antelopes or zebras.

“It is important to shine a light on these camelids,” concludes Godoy. “They do not often receive the attention they deserve. When you go to a national park, you hope to see a puma or the Andean mountain cat. But the guanacos are also part of that landscape. When you start to pay a little more attention to them, you realize these camelids are fascinating. They are also key to maintaining ecosystemic health, be it the bofedales of the altiplano, or on the Patagonian steppe. It is vital to provide camelids with the pedestal they deserve.”